A Story of Dad

We did our tour of the yard, as we always do. It’s the first thing he says to me usually, after our hello hugs. “Let’s take a garden tour!” And we do. I picked lemons, because that lemon tree has the finest lemons on it anywhere. Meyer lemons, of course. The tree is only a few years younger than I am.

Dad likes to sit in this chair in his garden. But when I asked him to, he wouldn’t, lol. Tomatoes on the far left and far right. Pole beans and sunflowers behind them.

We usually take our time, go from one corner of the small yard to the other, talking about what was growing, what he’d gotten rid of, what he wished he’d planted.

But this time he wears out fast. Pneumonia, he says. On meds. I’m fine, he says. I eye him. He’s thinner than the last time I saw him. Worn. So we retreat to the cool of the house and sit on the couch he and my mother had picked out years ago now. I’ve never liked that couch but I suppose it will live on long after I am gone. Some pieces of furniture are like that.

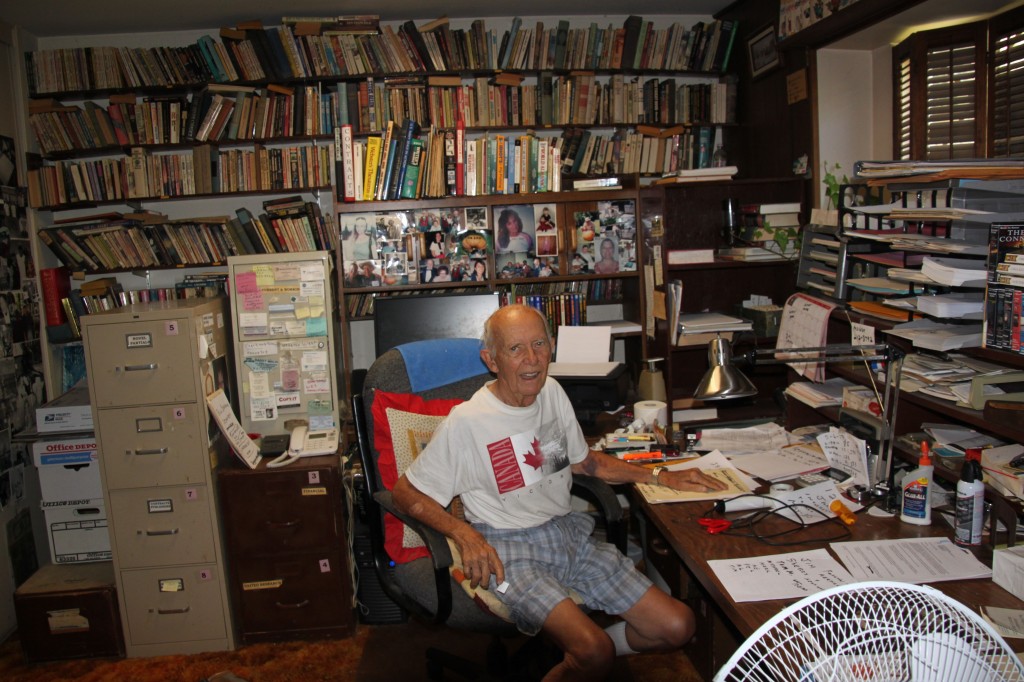

We sit there, holding hands. The skin on the back of his hand is so soft, loose. His fingers are gnarled by arthritis, and yet he still manages to type on a keyboard. We talk. He mentions a short story he wrote, a companion piece to the one he wrote about his dad, my grandpa. Grandpa sold off the family farm and equipment and livestock for pennies, so he could take his family out of Nebraska, escape the dust bowl of the late 1930s. That was dad’s original short story, about the sale. The new short story is about the journey to Oregon.

You remember it, don’t you? Living on the farm in Nebraska? I stroke his hand. So soft.

Not really, he answers. Just bizarre things, like Dad pouring kerosene down a cow’s throat because she was bloated. The kerosene helped the cow vomit up the bloat. Oh, and one time the neighbors gathered to castrate some of the piglets. Lots of screaming that day. Piglets are noisy.

And Mom, he says. When the time came to thresh the wheat, all the farm families would pitch in and hire the thresher, and everyone would go to a farm and get ‘er done. When our turn came, Mom would be cooking all day and she’d lay out a lunch on a huge table outside under the trees. Chickens and ham and steak, beans and whatever we’d grown in the house garden. Everyone would sit around and eat. Then the next day, they’d go to another farm and thresh their wheat.

But I didn’t do too much, he said. I was too little.

And then he pulls out of the past. I’m going to the Western Writers Association conference on Tuesday, he says. In Las Vegas. Jo will go with me, make sure I’m taking my pills.

I frown at him, but I know he won’t back down.

I’ve got nine projects to pitch, he says. Twelve or thirteen on the shelf that no one wants. But nine to pitch. I’ll sign up for as many pitch appointments as I can, he says.

Conferences can be really tiring, I say. Make sure you rest.

Oh, I’m on a panel, he says. But I won’t go to many workshops. Want to talk to people mostly.

We fall into a comfortable silence, our hands still holding on. I remember the last time I saw my mother, the day I put my head in her lap and cried because she looked so confused about life. A week later, she had died from an infection that got into her bloodstream.

Dad has pneumonia, and he’s going to a writer’s conference. It is so like him. I hold his hand gently, and engrave this memory, this time, this conversation with him, deep into my heart.